In San Cristóbal, Comal is about the food

One Mexican chef's lifelong journey with food.

Blue Bell ice cream. I’d be willing to bet this is one of the only times a story of a Mexican chef making simple yet extraordinary dishes in the highlands of Chiapas would start with Blue Bell ice cream. But for David Hernández of Comal, it did.

San Cristóbal de las Casas is a special place. It’s a small Spanish colonial city tucked into the southern highlands of Mexico, in the state of Chiapas, far removed from the usual tourist hotspots. If you've heard of San Cristóbal, you probably drink way too much coffee or know that Coca-Cola decided to wreak havoc and get its grubby little hands all over the region’s natural resources.

Most of San Cristóbal is mountainous, but the city is in a small valley. The weather is moderate year-round, and the food is good - life feels quiet and peaceful. When you’re there, it’s easy to forget about anything that sits beyond the hills surrounding the city. It’s an unsuspecting charm that grabs you and doesn’t let go.

Perhaps just as unsuspecting as San Cristóbal is a small restaurant on the eastern edge of the city center.

On a steep street is a white building with a corrugated metal roof and a simple wood sign that reads Comal, Cocina de Barro. When you enter the restaurant, mismatched chairs and tables are scattered throughout. On the right-hand side is an open kitchen (cocina de barro translates to "mud kitchen"), with a prep station on one side and a wood-fired comal (small griddle) on the other.

The menu is written on a small whiteboard placed at the front of the restaurant: tetelas, sopes, or quesadillas, all of which can be served with or without the daily salsas or toppings. There are also some dishes like a frijole de vara or guacamole, and a few drinks like pozol, tascalate, or café de olla (admittedly, I didn’t know what a few of those menu items were).

During your meal, you’ll see all the tables full of locals and some clearly not locals, a woman, Brenda, helping out in every way imaginable, and one chef, David, chopping and cooking away.

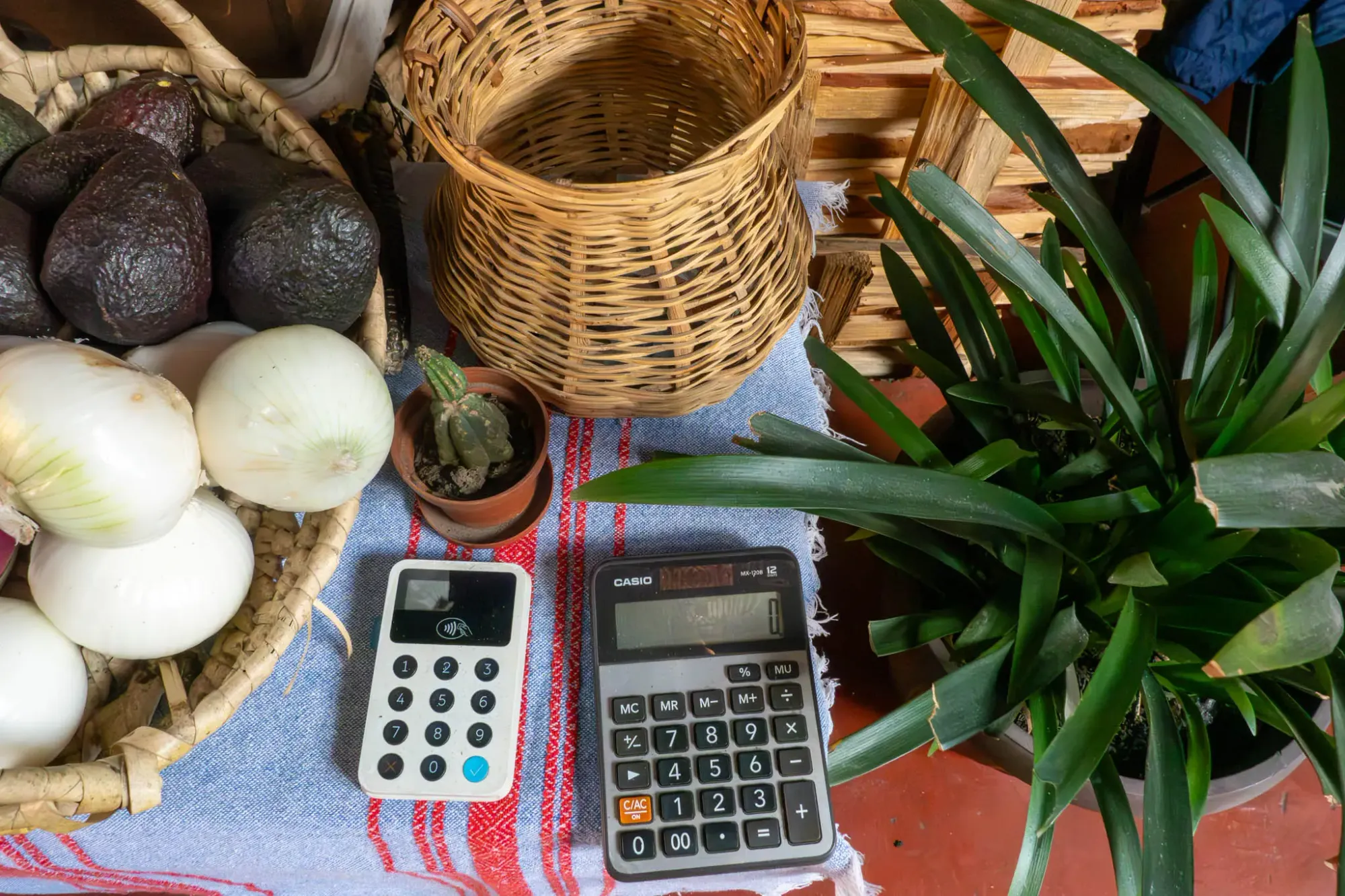

I could point to so many details of Comal that stood out to me: the impeccably delicious and understated food, the homey ambiance of the restaurant itself, the "here’s a calculator make your own bill" payment system, or the speech that David would have to recite every time some gringo would ask him questions about himself or his food.

But to understand any of the details, to understand Comal or the food served there, you first need to understand David.

David was born in Mexico City but didn’t do much growing up there. His parents separated when he was young, and David spent most of his time with his dad. His father’s work took him around Mexico, selling goods and wares at local markets throughout the country. Money was tight at the time, so dinners were often spent at small food stalls at those same markets.

By age 14, his mom had married a Texan and moved to the U.S. while his dad had settled in Cancún. And so, eager to continue traveling, David took a trip to see them in Austin, Texas. The way David tells the story, his journey with food started almost as soon as he stepped foot into the U.S.

“The first thing my stepdad asked was, have you tried Blue Bell ice cream? I was like, no, I don't know what that is. So I had the vanilla Blue Bell ice cream, like, I had a pint. I remember thinking this is so good.” David laughed as he recalled. “And that tasted like something that I’ve never eaten before in my life.”

What was supposed to be a three-week trip turned into 14 years. His stepfather’s job took them to Oklahoma, where he would attend high school (and college). Another formative food-related memory came during his first few days of school.

“When I was living with my dad, my money situation was pretty bad. So food was weird, you know, to get a hold of. So when I moved to the U.S., and I went to school the first few days when it was time to eat, I thought, I don’t know, I don’t have enough money. I didn't speak much English, but one friend said, 'Money? What do you mean just go get whatever you want.' Because I didn’t know food was free at the cafeteria.”

By age 24, he got a job at a photography company that took him all over the U.S., managing various studios across the country and living in more cities than most folks from the U.S. ever will. But after a few years, the paperwork and bureaucracy became too much, so he returned to Mexico.

Back in Cancún, his dad had opened a small restaurant called Bistro, where David went to help out for a bit as he thought about his next move. “He used to tell me, 'I don’t have money to give you when I die,' David remembered. ‘‘'I don't have anything to give you, but learn this recipe because this is your inheritance.'’’

Bistro would eventually close, and David found himself working as a bar back for another restaurant in Cancún - his first real foray into the restaurant industry. From there, he’d work his way up to bartender, then bar manager, and even a mixologist (though he still laughs at that title). For the next few years, he would work the hotel circuit between Playa del Carmen and Cancún, being poached by the likes of Thompson (and famed chef Pedro Abascal) to craft their bar menus.

And then, in 2020, COVID happened, putting his restaurant and bar work on an indefinite pause.

A year or so later, David moved to San Cristóbal de las Casas with his then-girlfriend but wasn’t having as much luck with the restaurant scene - nothing felt right. As COVID was subsiding and restaurants started to get busy again, he was about to head back to Playa del Carmen. But two weeks before he was planning to leave, his brother, also living in San Cristóbal at the time, stepped in.

“My brother was like, don’t go, sell food.”

So he got to work on Comal.

After all those years of eating and working in markets and restaurants across the U.S. and Mexico, David kept a mental tally of what he liked to eat and how he thought food should taste. So he got out his notebook and started sketching the initial plans for Comal.

“You know, what do I like to eat? Maybe I can do quesadillas.” He said. “And then the masa I make for the quesadilla is the same corn I use for the pozol. And it’s the same corn that I use for the tascalate. And so on. So like, I don’t have a lot of production.”

So with the initial vision in mind, David, living in his brother’s apartment at the time, set up shop on a corner near his apartment. Each day washing the sidewalk, prepping the food, and serving customers.

“I started on a Thursday, and by Sunday, I didn’t think I could keep going. I used to wake up at six in the morning and then go shopping, then come back, wash everything, clean everything, then do the masa, then do the salads, then do the salsa, and then go outside to wash the floor outside, then carry everything, and then the fire. And then, at night, bring everything back in. And then at the end of the night, wash all the dishes and then do all the shopping. Do all the numbers. I was working from six until one in the morning.”

But he kept at it. He hired a woman, Brenda, to help with some of the cleaning and prep work, which allowed him to tinker and experiment with the menu. And little by little, word spread, lines appeared, and he’d sell out of food. Eventually, he had to move the whole Comal operation into his brother’s house, where it is today.

Images of inside Comal restaurant.CC

At its best, food is a window into the soul of its maker. Comal is no different.

Each item on the menu represents a snapshot of moments in David’s life: the quesadilla from his time in Mexico City, the sope from Puebla, the tetela from Oaxaca, the pozol and tascalate from San Cristóbal, and the frijole de vara is a safeguarded recipe from his grandmother. All dishes are improvised and shaped by his experiences.

But the clearest look into the soul of Comal and its maker comes when you go to pay for your food. There’s no check, and no server is bringing you the bill. When you’re done, you calculate your tab using the prices on the small whiteboard up front and drop the pesos into a small wicker basket.

“I suppose that’s sort of how it started the first day. Somebody tried to pay while I was cooking,” David said, laughing. “And then I was like, my hands are dirty, just put it in the basket.” And they asked, how much was it? I just said oh, there’s a calculator, you know, do your thing. You can do your math.”

The idea stuck. Taking the transaction component out of the experience felt right for Comal, and it’s still how you pay today.

Like me, you might be wondering how often he’s been ripped off, but in two years, David said it’s extremely rare he’s missing money at the end of the night.

“If somebody needs it enough that they are going to take it, then just take it. You know, it will come back at some point. I’ve seen people throwing 500 pesos in the basket, so it all evens out.”

It’s telling, though, that a restauranteur didn’t think about handling payments before opening up shop, especially with the type of business we think of as having thin margins. But that’s the thing, for David, it’s always been about the food, never the money. It’s the same reason he doesn’t serve alcohol there (though you can bring your own if you feel so inclined), and it’s the same reason he won’t open the restaurant if he can’t find good enough ingredients at the market that day.

The way he recounts his experiences with food with such reverence, whether it’s eating at markets with his dad or tasting Blue Bell ice cream for the first time, it’s obvious those were formative moments for him. From what I can intuit, it would all be worth it if he could give those same experiences to people when they eat at Comal.

More insights from David

- Quesadillas in Mexico City DO NOT have cheese - welcome to an age-old debate about what actually defines a quesadilla.

- During the conversation, he said sometimes he feels like he’s selling salsa, not quesadillas or sopes. You can have an average tortilla and some meat, but it’s still delicious if you have good salsas. So never underestimate the importance of a good salsa.